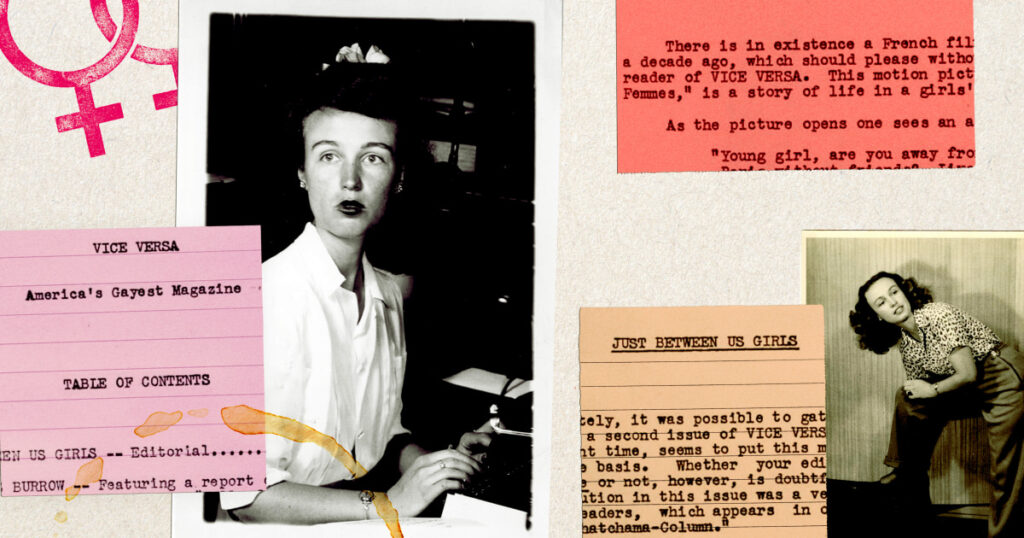

In 1947, Edythe Eyde was a secretary working at RKO Radio Pictures in Los Angeles. A speedy typist who often completed work ahead of schedule, her boss told her: “Well, I don’t care what you do if you get through with your work, but … don’t sit and read a magazine or knit. I want you to look busy.”

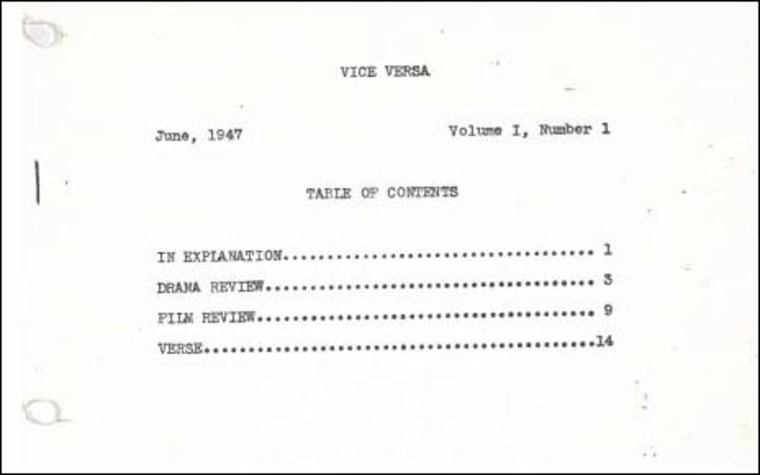

The literary-minded lesbian saw an opportunity. Gay culture was largely underground, and it was difficult for “the third sex” to meet like-minded others. Using a Royal manual typewriter and carbon paper, making six copies at a time, the 25-year-old launched Vice Versa — “a magazine dedicated, in all seriousness, to those of us who will never quite be able to adapt ourselves to the iron-bound rules of Convention.”

“During those days I didn’t really know many girls,” she told the lesbian magazine Visibilities in a 1990 interview. “But I thought, well, I’ll just keep turning out these magazines and maybe I’ll meet some!”

It worked. By Issue 4, the writer was awakened one night by readers tapping at her window. “Their enthusiasm was gratifying indeed,” she wrote.

Vice Versa featured original poems, short stories and reviews of books, films and plays; any dramatic work with the slightest undertone of attraction between women was fair game. Her “Watchama-Column” was a catch-all for her musings, and she invited others to sharpen their pencils and contribute.

Eyde distributed the photocopied magazine to friends, asking that they be passed along. (“But puh-leeze, let’s keep it ‘just between us girls.’”). She also sent copies by mail, until a friend warned of illegality; the Comstock Act forbade sending “obscene, lewd or lascivious” materials, without describing further.

“I don’t know if she understood when she started typing the magazine that you could get in trouble for distributing work like that,” said acclaimed historian Lillian Faderman, author of “The Gay Revolution.” “It was a sort of blessed naivete, I think, that made it possible for her to do that.”

From June 1947 to February 1948, Eyde produced nine monthly issues, stopping only when Howard Hughes bought the studio and new work in secretarial pools did not afford privacy or extra time. She could not have known then that her humble magazine would be heralded well into the next century as a first in the lineage of lavender press.

“It was revolutionary,” Faderman said of Vice Versa. “I don’t think she realized how revolutionary it was. I don’t think she realized how brave and meaningful it was.”

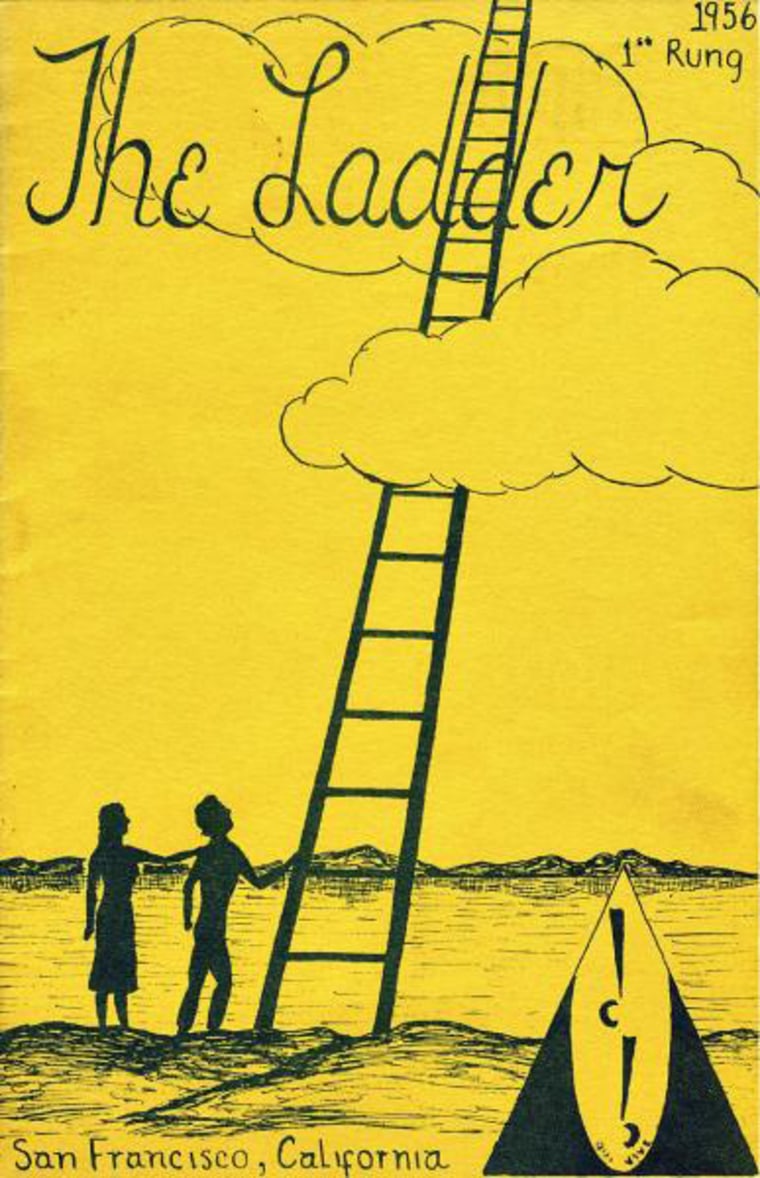

Faderman noted that Vice Versa inspired several female writers, who took courage from Eyde’s friendship and undertaking, to contribute content to the male-centric ONE Magazine, which launched in 1953 (and in 1958 was at the center of a landmark Supreme Court case that protected free speech around homosexuality). In the mid-1950s, Eyde also got involved with the first lesbian rights organization, Daughters of Bilitis. Adopting the name Lisa Ben (a clever anagram of “lesbian”), she contributed to the organization’s magazine, The Ladder — the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the U.S., which ran from 1956 through 1972.

“It was a very brave little magazine, and I was happy to be a part of it,” she said of The Ladder in a 1988 interview with Manuela Soares for the Daughters of Bilitis Video Project at the Lesbian Herstory Archives. “I was bubbling over with this sense of gayness, and it was easy to transpose it onto paper and send it in.”

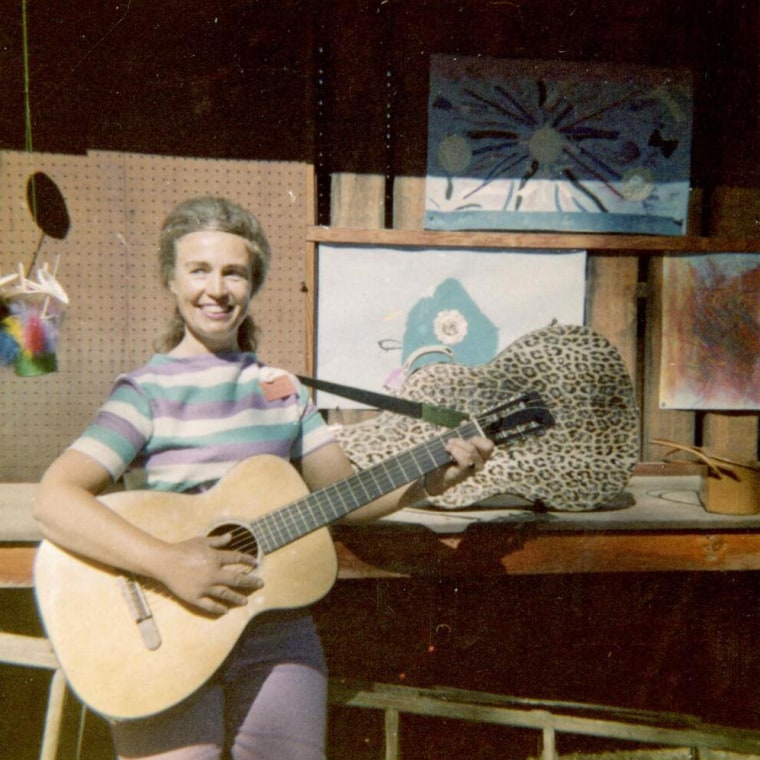

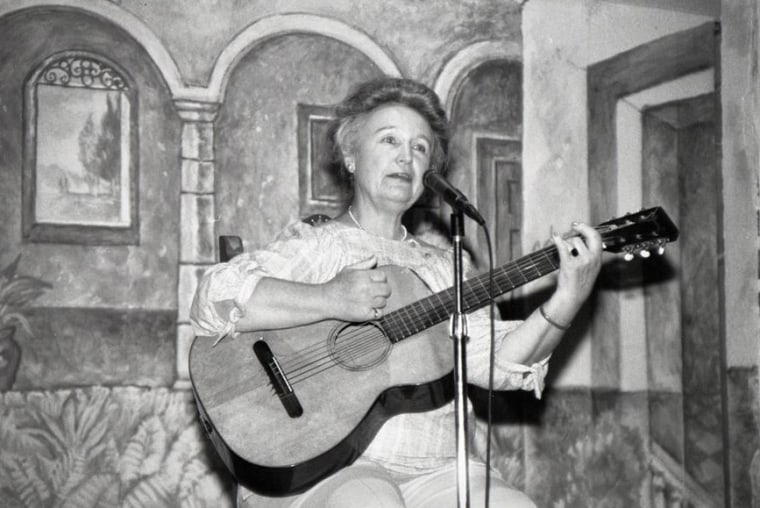

Eyde’s brand of activism was not overt, though her talents were wide-reaching, and she used creativity as a counterpoint to society’s disdain “of our inclinations,” as she called them in Vice Versa. An assiduous student of the violin in earlier years, Eyde took up guitar for a cause.

The inspiration took root at a West Hollywood drag bar Club Flamingo, which drew gay people in the afternoon and, toward the evening, a broad audience who enjoyed impersonations of Golden Age divas. Eyde stayed late one night and was horrified by the “filth” she witnessed, particularly the willingness of gay performers to “debase” themselves — and, specifically, lesbian nightclub singer Beverly Shaw — to get laughs from the general public.

Eyde set to writing parodies that cast gays and lesbians in a positive light. She performed at parties and private homes.

“Gee, my phone rang off the wall,” she told Soares. “I would bring my guitar and sing all these gay parodies — and I had an awful lot of fun doing that.”

As for those lesbian pulp novels, she told Soares she “read as many as I could get my greedy little hands on.”

“It was so nice to be able to read things like that and not have parents breathing down my neck,” she said. As a teen, her overbearing parents even monitored her library books.

“Her parents were very conservative,” recalled Vicky Venhuizen, 81, a distant cousin by marriage. Venhuizen met Eyde when the writer came to Rockford, Illinois, with her parents.

“My impression … was that she was glamorous,” Venhuizen said, noting that she was in awe of Eyde’s independence. “She was unmarried, which was rare for a ’50s kid like me, and she lived in California.”

“She was ahead of her time,” Venhuizen said. “Her writings proved that.”

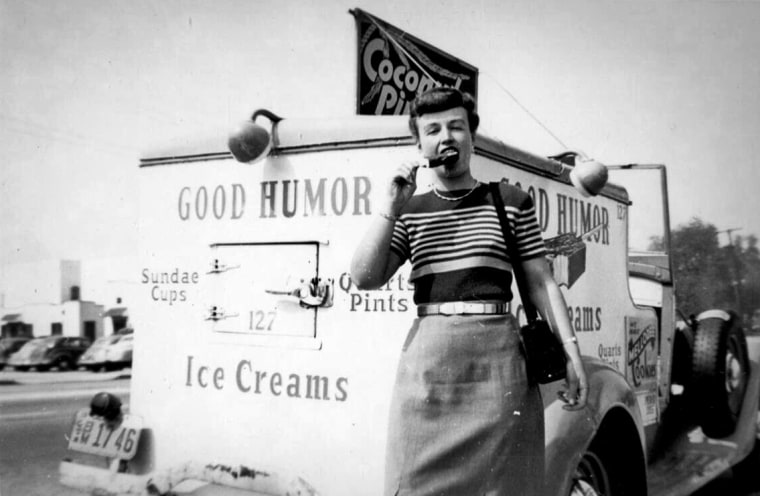

Though not identifying as a SciFi writer, Edye was an enthusiastic consumer of horror stories and fantasy; a card-carrying member of the Fourth World Science Fiction Convention Society; and, to the delight of the modern admirer, can be seen in a 1945 photo in a bikini top reading the pulp magazine Weird Tales.

She preferred frilly dresses over trousers and loved dancing with the “gay gals” at the If Club, a low-lit Los Angeles bar considered safe for the butches that she favored — and great spot to distribute Vice Versa.

Eyde “ran with a hard-drinking crowd,” but she didn’t care for alcohol herself. In a 1995 interview, Eyde recalled meeting a gorgeous girl at a party who wasn’t fit to drive her home: “She was a hell of a lover — golly, she was great, and I enjoyed being with her and all that, but she just couldn’t leave the booze alone: couldn’t drive the stick shift.”

Eyde maintained her vivacious spirit over the decades. In 1989, Eric Marcus, creator of the Making Gay History podcast, tracked her down in her small Burbank bungalow, attained through many years of secretarial work and frugal living.

“She was absolutely charming,” Marcus said of Eyde, then 68. “She had curly hair and was very girlish in a lovely, charming way — very welcoming and eager to talk and happy to play her music for me.”

As an only child on a fruit ranch in Los Altos, California, her friends had been animals — a dog and cat, then later, a goat and riding pony. So, too, in later years, she settled into a quiet isolated life, caregiver to 15 cats.

Edythe Eyde, aka Lisa Ben, was inducted into The Association LGBTQ+ Journalists’ Hall of Fame in 2010, and in 2015, she received the association’s first Lisa Ben Award for Achievement in Features Coverage. She died later that year, at 94.

She may never have fully appreciated her own courage, but it appeared she knew no other way.

“My feelings in such matters have always seemed quite natural and ‘right’ to me,” she wrote. “Right” like that exquisite time that she never did let go of — when a wavy-haired high school girl took her in her arms to dance around the living room. “As our acquaintance grew, we found out how pleasant it was to kiss one another and hug one another … and I just really thought she was tops. I just loved her.”

More Stories

Longtime Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin will not seek re-election in 2026

Trump’s treasury secretary says plan is not for ‘America alone,’ but reiterates focus on trade deficits

California homeowners allege home insurance companies colluded to deny coverage