Business reporter

Femern

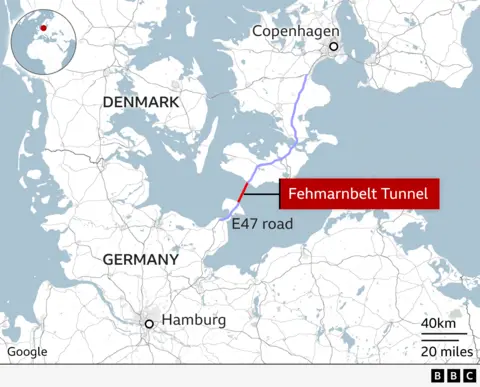

FemernA record-breaking tunnel is being built under the Baltic Sea between Denmark and Germany, which will slash travel times and improve Scandinavia’s links with the rest of Europe.

Running for 18km (11 miles), the Fehmarnbelt will be the world’s longest pre-fabricated road and rail tunnel.

It’s also a remarkable feat of engineering, that will see segments of the tunnel placed on top of the seafloor, and then joined together.

The project’s main construction site is located at the northern entrance to the tunnel, on the coast of Lolland island in the south east of Denmark.

The facility spans more than 500 hectares (1,235 acres), and includes a harbour and a factory that is manufacturing the tunnel sections, which are called “elements”.

“It’s a huge facility here,” says Henrik Vincentsen, chief executive of Femern, the state-owned Danish company that is building the tunnel.

To make each 217m (712ft) long and 42m wide element reinforced steel is cast with concrete.

Most underwater tunnels – including the 50km Channel Tunnel between the UK and France – burrow through bedrock beneath the seafloor. Here instead, 90 individual elements will be linked up, piece by piece, like Lego bricks.

“We are breaking records with this project,” says Mr Vincentsen. “Immersed tunnels have been built before, but never on this scale.”

With a price-tag around €7.4bn ($8.1bn; £6.3bn) the scheme has mostly been financed by Denmark, with €1.3bn from the European Commission.

It’s among the region’s largest-ever infrastructure projects, and part of a wider EU plan to strengthen travel links across the continent while reducing flying.

Once completed, the journey between Rødbyhavn in southern Denmark and Puttgarten in northern Germany, will take just 10 minutes by car, or seven minutes by train, replacing a 45-minute ferry voyage.

Bypassing western Denmark, the new rail route will also halve travel times between Copenhagen and Hamburg from five to 2.5 hours, and provide a “greener” shortcut for freight and passengers.

“It’s not only linking Denmark to Germany, it’s linking Scandinavia to central Europe,” states Mr Vincentsen. “Everybody’s a winner,” he claims. “And by travelling 160km less, you’ll also cut carbon and reduce the impact of transport.”

Towered over by cranes, the tunnel entrance sits at the base of a steep coastal wall with sparkling seawater lying overhead.

“So now we are in the first part of the tunnel,” announces senior construction manager Anders Gert Wede, as we walk inside the future highway. It’s one of five parallel tubes in each element.

There are two for railway lines, two for roads (which have two lanes in each direction), and a maintenance and emergency corridor.

At the other end enormous steel doors hold back the sea. “As you can hear, it’s quite thick,” he says tapping on the metal. “When we have a finished element at the harbour, it will be towed out to the location and then we will slowly immerse it behind the steel doors here.”

Not only are these elements long, they’re enormously heavy, weighing over 73,000 tonnes. Yet incredibly, sealing the ends watertight and fitting them with ballast tanks, gives enough buoyancy to tow them behind tugboats.

Next it’s a painstakingly complex procedure, lowering the elements 40 metres down into a trench dug out on the seafloor, using underwater cameras and GPS-guided equipment, to line it up with 15mm precision.

“We have to be very, very careful,” emphasises Mr Wede. “We have a system called ‘pin and catch’ where you have a V-shaped structure and some arms grabbing onto the element, dragging it slowly into place.”

Femern

FemernDenmark sits at the mouth of the Baltic, on a stretch of sea with busy shipping lanes.

With layers of clay and bedrock of chalk, the subsurface is too soft to drill a bore tunnel, said Per Goltermann, a professor in concrete and structures at the Technical University of Denmark.

A bridge was initially considered, but strong winds might disrupt traffic, and security was another important consideration.

“There was the risk of ships crashing into bridges. We can build the bridge so they can withstand it,” he adds. “But this is rather deep water, and the biggest ships can sail there.”

So, adds Mr Goltermann, it was decided to go with an immersed tunnel. “They looked at it and said, “Okay, what is the cheapest? The tunnel. What is the safest? The tunnel.”

Denmark and Germany signed an agreement to build the tunnel back in 2008, but the scheme was delayed by opposition from ferry operators and German conservation groups concerned about the ecological impact.

One such environmental group, Nabu (The Nature And Biodiversity Conservation Union), argued that this area of the Baltic is an important habitat for larvae and harbour porpoises, which are sensitive to underwater noise.

However in 2020 their legal challenge was dismissed by a federal court in Germany, which green-lighted construction to go ahead.

“We have done a lot of initiatives to make sure that the impact of this project is as small as possible,” says Mr Vincentsen, pointing to a 300-hectare wetland nature and recreational area that’s planned on reclaimed land, which has been built from the dredged up sand and rock.

When the tunnel opens in 2029, Femern estimates that more than 100 trains and 12,000 cars will use it each day.

According to plans, revenues collected from toll fees will repay the state-backed loans that were taken out to finance the construction, and Mr Vincentsen calculates that will take around four decades. “Ultimately, the users are going to pay,” he says.

It’s also hoped the huge investment will boost jobs, business and tourism in Lolland, which is one of Denmark’s poorest regions.

“The locals down here have been waiting for this project for a lot of years,” said Mr Wede, who grew up nearby. “They’re looking forward to businesses coming to the area.”

More Stories

Tesla profits plunge amid Musk backlash

Adani drops telecom plans, will sell spectrum to Airtel | India News

Gold fever: Futures top Rs 1L/10gm mark